Progress Report: One Month After Starting From Scratch With How To Train Dog Recall

When you call your dog to come in a variety of settings, how likely are they to immediately run to you? If you’ve been following along, you’ll know that I “started over” with my “hunty-sniffy” dog Sully’s recall about a month ago.

In my first article, I talked about what recall actually is, why I changed Sully’s recall cue, and how I started working with the new cue (among other things). In my second article, I talked about my effort to capture and build attention as a foundation for recall.

What changes have I seen in the past month (keep scrolling!)? What am I keeping an eye on? Let’s dig into my one-month update!

Recall Priorities: Build Behavior First

Before I started from scratch with working on recall with Sully, she used to routinely side step around me in the woods like I was an obstacle to avoid in her sniffing path.

While I introduced a new recall cue to Sully (you can learn more about that process here) a month ago, I’ve actually devoted very little of my time and energy to training with that recall cue. I’ve done two formal training sessions with it and paired it with human food she loves (as the opportunity arose) if I was planning to share with her anyway. That’s it.

The vast majority of my effort this month has gone towards building desired behavior on trails without any verbal cues.

There are three main behaviors I’ve been focused on:

Offering attention (i.e. voluntarily looking at me or orienting to me)

Coming all the way to me when I mark or drop a treat on the ground

Eating the treat I offer

I talked about this process more in my previous article, but as a refresher, here’s what I’ve been doing for the past month:

On our daily trail walks, we stop at least once to play a simple attention game (it’s quick - usually no more than 30 seconds). Sometimes it’s a stationary up-down game while other times it involves more movement. (You can see quick examples of stationary and moving games we play in this post we shared. I also shared how-to’s at the very bottom of this article. Plus, if you really wanna work on attention, check out our on-demand video e-course, Attention Unlocked!)

On our daily trail walks, we capture any and all attention that she offers. Literally. Every single instance. That means that if she stops and orients to us or looks at us, we give her a treat.

In Recall Training The Secret Sauce Is ‘Simple Is Sustainable’

Perhaps you noticed that nothing that I’m doing is earth shattering. Maybe you noticed that I’ve done almost no “formal training sessions.”. The bulk of my work is happening on our trail walks - an activity that is already a habit for me. This is intentional and here’s why:

Foundations first. If I can’t get some of the “simpler behaviors” to show up, I set us up for failure if I move past them. Plus, just because I know how to do “more complex” things doesn’t mean that is what I should be doing. Our progress has come from consistently working on simple foundations.

You want to see change? Then you generally need consistency. And I know that I do simple things more consistently than complex things. It’s harder for me to consistently carve out training sessions from my day than it is to pause for 30 seconds on a walk (especially with Sully – I have much less of an R+ history for training her than I do with my other dog, Otis). So I do what I know I can do consistently.

How To Make Magic: Collect Data

When I first started talking about our recall journey, I mentioned wanting to do this systematically – including taking data. Data are really important to the training process. They help us determine how to intervene and if our interventions are working as expected.

Given all the effort I am putting into building attention, how do I know “if it’s working”?

DATA!!!

I have been measuring the number of instances of “offered attention” per daily hour-long walk. I defined an instance of “offered attention” as Sully looking at us (eye contact), stopping and turning at least her head towards us (with or without eye contact), and/or walking up to us and pausing (with or without eye contact). Anecdotally, the majority of her instances include eye contact. (Some dogs don’t love eye contact, so I am fine with a general orienting behavior.)

Admittedly, I am not being as precise as I could be. I keep count in my head as we walk and jot down the total on my phone at the end of the walk. I undoubtedly screw up my counts, but ultimately, this isn’t a formal study. I am just looking to get a sense of the overall trend (I want to see the count trending upward).

When I first started this journey, this number was so low (between zero and three) that it was easy to count. It’s gone up so much over the past month (now she regularly offers around 30 instances of attention per daily hour-long trail walk) that I likely need to revise my data strategy.

If I wasn’t seeing her offer more attention on walks, I would have revised my strategy.

Behavior Update: A Quick Summary

Sometimes you gotta start slow to go fast in the end. My partner, Ben, and I have been getting such a kick out of the changes we are seeing in Sully after a month of work (remember: we didn’t do any fancy training; we just did simple stuff consistently).

Typical Number of Instances of Offered Attention Per Hour-Long Walk

One Month Ago: 0 to 3

Today: ~ 30

When we’re walking together, I have gone from an obstacle for Sully to avoid in her sniffing path to a signal for valued reinforcers in many contexts. I won’t lie: that feels nice 😂.

Many of the check-ins she offers happen when she is within 15 feet of us (she’s rarely farther than that because that’s the length of her dragline). However, the other day she was in pursuit of some poop to roll in and got a bit farther away from us. I knew I had no business trying to call her, so I just waited. And guess what she did after she rolled in the poop for 10 seconds? She SPRINTED the 30 yards to me. Everything about her behavior gave me the sense that she was certain she would get a treat when she showed up to me. This is what I want! It tells me that contingencies are clear and that my reinforcers are competing well enough in this environment. In an ideal world, I see this type of “recall behavior” show up more and more before I ever add a verbal cue.

Guess what else I am seeing?! When we verbally prompt her (with her name or a kissy noise), she is responding by orienting to or coming to us more often. Now to be fair, I am not measuring these data right now, so I am just going off what I think I have noticed (but given that she was basically unresponsive most of the time a month ago, it’s not hard to see the change). You can see a clear example of this at the end of this post we shared this week where I said her name to simply see if she could look at me (she chose to run all the way to me).

Will Your Treats Compete?

If you have a dog who doesn’t consistently eat outside, please know you are in good company. That used to be Sully. And it could be Sully again tomorrow if I don’t set her up for success (by that I mean arrange conditions in ways that I know make it likely for her to perform the eating behavior).

For the past month, we’ve been primarily using boiled shredded chicken breasts, baked chicken thighs, or ground beef as our treats, and she has consistently been eating them. We only use these as treats when we do our trail walks to try to reap some of the benefits of novelty when it comes to reinforcer value (without using food deprivation). The novelty can boost the value of reinforcers, which can help them compete with nature, increase the reinforcing strength of the treat, and make eating behavior more likely (as well as any behavior that produces the opportunity to eat).

I spent a number of months (a while ago) focused on building her eating behavior, but I still have to be careful. I am intentional in how I progress to make it more likely for my treats to compete. For example, when I first started working on attention pattern games (a while ago), we played indoors with very few distractions so that the desired behaviors were likely to show up. Then we slowly moved to more distracting settings (only as fast as I could keep the desired behavior stable). Now those patterns games are ones I can use in new environments to help get eating behavior to show up there (since the eating behavior already shows up in those pattern games under generalized conditions).

On a day when I only have string cheese (which is still high value but less novel), I am less likely to offer food early in the walk. Early in the walk, nature is more novel and therefore higher value, and cheese doesn’t compete as well. After about 15 to 20 minutes, I can count on her eating cheese.

The precursor to everything I have been talking about is having a reinforcer that your dog will reliably perform to access. In my case, that’s food, which means I need to count on Sully coming towards me to eat the food (that’s a behavior) when I offer it on trails before I can really use food as a reinforcer on trails. If you aren’t getting the eating behavior consistently when you just offer “free food,” you likely need to change your antecedents. Where will your dog consistently eat the food you offer? Start there and then bring the behavior into new environments. (Note: I am just thinking out loud here because this comes up so often. I am not giving specific advice. One of the first things you should check if your dog is not eating consistently is their health..)

Fringe Benefits

Historically, I haven’t always loved training Sully. She doesn’t opt into training as often around home (she prefers to sleep under an old poplar tree or patrol the yard) and tends to offer fewer behaviors that I find really reinforcing (like looking at me, coming to me, asking me for attention). I just have less of a reinforcement history for working with her than I do with Otis. One of the real benefits of focusing so much on capturing attention has been how much reinforcement I am getting from this for “training” her. I am seeing behaviors I love more (since I am looking for them and then reinforcing them). I now have a nice, recent R+ history as I approach the next phase.

What’s Next?

I will keep reinforcing the heck out of attention on our walks, but I am likely going to put a bit more effort into working on recall using our new verbal cue around home, where I can control the level of distraction. Stay tuned!

Reminder

I am very realistic when it comes to Sully. I don’t expect to turn her into Otis. I expect to make progress, but my goal is not to create a dog who stares at me all of the time. She is still my “wild child,” and I wouldn’t have it any other way. I anticipate that I will always be a bit choosy about where I drop her dragline and what criteria I have for that decision, and that is perfectly okay for us!

Addendum: My Go-to Simple Attention Games on Walks

I like to pause like this on hikes now to play attention games with Sully (Otis insists on joining in the fun too!) like the up-down pattern game seen above.

A number of people asked in an Instagram post this week what attention games I play on walks, so I am sharing the two most common ones here!

Simple Up-Down Pattern Game (popularized by Leslie McDevvit)

To play:

Place a treat down on the ground in front of your dog’s paws for them to eat.

When they eat it, they should naturally lift their head up. Mark (you can say “yes” or use a location specific marker like “find it”) and reinforce (place another treat down in the same spot in front of your dog’s paws.

Quietly wait for them to orient up towards you. (Many dogs will look up at you, but if that is uncomfortable for your dog, general orientation towards you works just as well!)

When they do look/orient to you, mark and reinforce with another treat in the same spot. Keep repeating.

Tips:

This game is about capturing offered attention, so you want to avoid prompting your dog by saying their name or pointing to your eyes.

Your dog is allowed to look around. Just wait for them to look up.

If they aren’t looking up at you consistently, you may need to start in a lower distraction environment.

Pattern Game with Movement

To play:

Place a couple treats down on the ground and then move away (if you’re just starting, take only a few steps, but if your dog knows this, you can move farther away).

After your dog eats the treats you put on the ground, they will look at you. Mark and reinforce by putting treats down on the ground where you’re standing and then move away again.

Repeat.

Keep it small or make it a bigger game with more running!

Tips:

Just like in the up-down pattern game, you are capturing offered behavior rather than verbally prompting your dog to come to you (though you could adapt the game to that end in the future!) In other words, do not say your dog’s name or their recall cue (for now).

How To Train a Dog To Recall Through Building Foundations

Do you dream of the day that your dog reliably comes (“recalls”) when you call them? Or maybe you’d just settle for an improvement relative to where you are right now. I recently decided that the best thing I could do to improve my little hunty-sniffy dog’s recall was to start over, and I’m bringing you along for the ride!

In my previous article, I talked about what recall actually is, why I changed Sully’s recall cue, and how I started working with the new cue (among other things). While I plan to systematically work on her response to that new cue (“Ewok”), today, I want to talk about the training that I’m doing simultaneously that doesn’t involve any verbal cues at all. We’re going back to foundations! (Pssst … I cannot emphasize enough how much the training in our on-demand video e-course, Attention Unlocked, can help with recall goals).

Forget the Recall Cue (For a Minute)! What Behavior Is My Dog Voluntarily Offering?

Let me start by painting a picture for you of my two dogs’, Otis and Sully, typically offered behaviors on trail walks (aka what they do voluntarily rather than in response to a verbal cue). As you read, consider which dog’s history may make them more likely to recall and why.

This is a pretty accurate depiction of the different behavioral tendencies of my two dogs. There is no good vs. bad or right vs. wrong here - just different. These dogs are individuals with vastly different learning histories. I love that Sully loves nature so much and my goal is not to turn her into Otis.

OTIS: Otis trots along trails sniffing specific spots or air scenting (aka throwing his nose in the air and following some invisible scent through space) and tends to stay in a roughly 15 yard radius from me. If he hits the edge of that radius, he either voluntarily stops and looks back at me or runs all the way to me, which I usually reinforce with a treat. As he trots along within that radius, he regularly looks back over his shoulder to see where I am or returns all the way to me to check-in, which I tend to reinforce with a small treat. If he sees another dog or person on the trail, he automatically stops and orients to me, which I tend to mark and reinforce. If I stop walking, he stops walking and looks at me. If I continue to stand still, he runs to me. If I change directions, so does he. If he hears a treat bag rustle or sees my hand move towards my treat bag, he sprints to me. If I give Sully a treat, Otis shows up.

SULLY: Sully moves with her nose glued to the ground for the vast majority of her walk. She has gone entire trail walks without ever once looking up at me (no joke). If I stop ahead of her in the middle of the trail, she will arc around my legs and carry on sniffing as if I am a rock and she is the river that just flows around it. She has been known to walk right past treats offered to her in open palms early on in walks. When I give Otis a treat, she appears oblivious by the way she carries on walking and sniffing right past the whole event. If she is not sniffing, she is likely staring at some prey she saw or heard.

Chances are you determined that Otis is likely better positioned (at least based on the limited info I gave you) to respond to recall cues on trails than Sully. How did you conclude that since I didn't talk at all about calling them to come? You probably picked up on the fact that Otis is already regularly offering components of the recall behavior on walks, which means those behaviors are getting regularly reinforced in that context. Plus, if my dog is behaving to access my reinforcers, I may have a bit more confidence in my ability to actually reinforce recall in the future (clearly, I needed to make adjustments with Sully).

What Are the Foundations for Recall?

This is a clip of my two dogs, Otis (gray and white) and Sully (blonde), and my neighbor's dog, Chance (white), on a hike. There were clearly some interesting smells in that area that they all picked up on, which thrills me! I want them to have the chance to move and explore without focusing on me. But notice how Otis voluntarily runs to me after he’s done sniffing? The environment cues those check-ins all the time with him. With Otis, I also feel confident saying that my treats compete easily with most of nature most of the time since he often behaves to access them. This type of history is really helpful when it comes to recall!

“Attention” (i.e. orienting to you) is one of the most important foundations for recall. I want to see a dog offering attention in the environments where I will use their recall cue in the future. Ultimately, it’s easier to recall a dog who is attuned to you to some degree (even if it’s just an occasional glance back) than one who has all of their senses fully tuned to the environment all the time. But perhaps more importantly, attention is the first behavior in the chain of behaviors that make up recall.

When you call your dog, they have to stop (if they are moving) and orient to you before they ever run to you (that is basically how we define “attention”).

I put a lot of weight (in the form of a positive reinforcement history) behind offered attention because I want that behavior to show up more often outdoors. By focusing on offered attention (aka no verbal prompt), I can reinforce part(s) of their recall behavior while mitigating the risk of using their recall cue when they’re not capable of responding, which would just weaken it. Plus, depending on when I mark and how/where I reinforce, I can actually produce more of the full recall behavior. For example, if my dog looks at me when they are 10 yards away from me on the trail, and I say “yes,” that marker cue essentially pulls my dog all the way into me. From the outside, it will look just like recall!

There is another foundation that is often overlooked. It’s easy to focus so much on the recall behavior that you take for granted the behaviors needed to actually access your reinforcers. Imagine you call your dog, and they run to you. When they get to you, you offer a treat in your palm. Your dog looks at it and decides to return to sniffing instead of eating it. You were hoping to reinforce their recall with a treat (we might say that “giving them a treat to take from your hand” was your “reinforcement strategy”), but they have to perform behaviors (approach hand, open mouth, grab treat, swallow treat) to actually “get the treat.” This leads to the other foundation I want to highlight in this article: Your dog needs to reliably (in a variety of environments) respond to the cues and perform the behaviors associated with the reinforcement strategies you plan to use with your dog’s recall. Put actionably, you likely want to practice your reinforcement strategies (in a variety of environments) before trying to use them to reinforce behaviors. Now put more plainly … think about how you plan to reinforce your dog’s recall – for example, dropped treats, tossed toy, etc. – and practice having your dog eat dropped treats or chase a dropped toy in various environments without those valuable events being contingent on some behavior like recall. If your dog doesn’t reliably eat food on trails, then you won’t really be able to use treats reliably to reinforce recall.

Markers are conditioned reinforcers, but they are also cues. That means if we plan to use markers, which I recommend as a general practice in training, we need to make sure our dogs can perform the behavior that the marker cues to actually access the reinforcer. In this video, I marked Sully’s offered attention by saying “yes,” which should tell her to come and get a treat from me. The first time I said “yes,” she started to move but then stopped. The second time I said “yes,” she flew to me to get the treat that “yes” told her was available. Ideally, I don’t ever want to use my marker without it being followed up by the associated primary reinforcer (this pairing needs to remain tight and consistent), so I want to be careful about only using it in conditions where I am confident that my dog can actually respond to get the treat (or whatever reinforcer my marker signals). I am way more careful about when I use my marker with Sully now.

Your reinforcement strategies may or may not include the use of markers like the word “yes” or a click from a clicker. Markers are a fairly complex topic that I am not going to dive into too deeply here, but feel free to check out this Instagram post I did talking about markers. I bring this up because strong markers allow you to capture offered attention from a greater distance. The marker serves as a secondary reinforcer for the offered attention (i.e. looking back at you) and a cue that brings your dog all the way back to you to access a primary reinforcer (i.e. a treat). However, in order to do this, not only does your dog need to be able to perform the eating behavior, they need to reliably respond to your markers. With some dogs, they’ll almost “automatically” respond to their known markers in just about every environment, but for many dogs, you have to train your markers in new environments to get your dog to respond to them there.

How Do I Get My Dog To Offer Me More Attention?

It’s easy to think that recall training is all about calling our dogs, them coming, and then reinforcing that behavior. But there are a lot of other things we can do that can improve their recall! For example, just about any training you do is going to up the level of reinforcement your dog has for working with you, being near you, responding to you, etc., and that history can absolutely help make it more likely for them to come to you when you call them.

I am using a few strategies right now to get Sully to offer me more attention on our trail walks, but I could boil them down to this: I’m reinforcing the heck out of it! Here’s a closer look at what I’ve been doing (you can see some of these in action in this IG post we shared):

1. We pause once on our daily walks to play the up-down pattern game (popularized by Leslie McDevvit) for 30 seconds or so. I love this game because it’s simple, sets the stage for her to offer attention (the pattern helps), and allows me to reinforce a lot of reps of offered attention pretty quickly!

To play:

Place a treat down on the ground in front of your dog’s paws for them to eat.

When they eat it, they should naturally lift their head up. Mark (you can say “yes” or use a location specific marker like “find it”) and reinforce (place another treat down in the same spot in front of your dog’s paws.

Quietly wait for them to orient up towards you. (Many dogs will look up at you, but if that is uncomfortable for your dog, general orientation towards you works just as well!)

When they do look/orient to you, mark and reinforce with another treat in the same spot. Keep repeating.

Tips:

This game is about capturing offered attention, so you want to avoid prompting your dog by saying their name or pointing to your eyes.

Your dog is allowed to look around. Just wait for them to look up.

If they aren’t looking up at you consistently, you may need to start in a lower distraction environment.

2. We pause on walks for 30 - 60 seconds to play moving pattern games. These games give Sully a chance to practice actually running to me.

To play:

Place a couple treats down on the ground and then move away (if you’re just starting, take only a few steps, but if your dog knows this, you can move farther away).

After your dog eats the treats you put on the ground, they will look at you. Mark and reinforce by putting treats down on the ground where you’re standing and then move away again.

Repeat.

Keep it small or make it a bigger game with more running!

Tips:

Just like in the up-down pattern game, you are capturing offered behavior rather than verbally prompting your dog to come to you (though you could adapt the game to that end in the future!) In other words, do not say your dog’s name or their recall cue (for now).

3. We capture any and all offered attention as we walk. That means literally anytime Sully intentionally chooses to orient towards us, we mark and give a treat (or just give a treat). This isn’t a behavior that has been showing up much on walks, but we are hoping to see more of it after adding the three items on this list to our walking routine.

We actually made a whole on-demand video e-course called Attention Unlocked with Juliana DeWillems of JW Dog Training to teach you how to build attention from the ground up (you would start farther back than what I am talking about in this article). Attention may not sound that sexy, but it’s the foundation for so many other behaviors (including recall). You will often reap big rewards by spending time on foundations (even if it feels “easy”) - we truly cannot recommend it enough.

The three things I am doing right now are very low lift, which is key if I want to reliably do them. More broadly speaking, these activities have dramatically increased my reinforcement level with Sully. One of the indirect factors that often helps a dog’s recall is just a large R+ history for interacting with that person, being near that person, etc. I want being near me to predict GREAT things for Sully, and since dogs are always learning, even basically any training can improve recall (this is why so many people who did the TOC Challenge reported that their dog was coming when called so much better even though there is no recall in that course).

Right now, I am just trying to get SOME offered attention on walks. In the future, I may incorporate some stimulus-stimulus pairing procedures to help produce more offered attention at certain points on our walks. For example, I may drop treats anytime I stop walking (pairing my stopping with treats on the ground) to try to produce the operant behavior of her standing near me. Or maybe I’ll start dropping treats anytime she hears a squirrel moving to get squirrels to become a cue to orient to me. Or maybe I’ll pull a page from Attention Unlocked book and work on offered attention around specific distractions. We shall see … for now, we are starting nice and simple and just trying to get attention to show up in the context of the woods!

Do you have a dog who will wake up from a deep sleep and come over to you if you even open the treat drawer? This is very much related to recall! One day I realized that anytime I opened a certain type of Tupperware, both of my dogs showed up in front of me. This is a great example of operant behavior (walking to me) that was produced by stimulus-stimulus pairing. Now to be honest, I am not sure where the pairing actually started. Was it the smell of chicken that got paired with me handing them chicken? Was it the sound of the lid that got paired with the smell of food, which might have already had its own associated response? Was it the sound of the lid that got paired with me handing them food? At any rate, the sound of that lid became a cue that signaled to them that if they came to me, I would hand them food. This is a reminder that our dogs are always learning by consequence and by association. The way to build a recall cue that’s as strong as the sound of treats or Tupperware lids is to make our recall cues reliable predictors of GREAT things.

How Can I Make Desired Behaviors More Likely?

We know that dogs perform behaviors more often if they lead to valued reinforcers. But the challenge is that the value of a stimulus or event is not static.

Let’s look at a human example. Imagine you got lost hiking in the woods and walked eight miles without any food. How valuable might a giant burger be to you in that moment? Now imagine you just ate a huge brunch and had to unbutton your pants to give your belly some room. How valuable might that exact same burger be in this post-brunch moment? Is it as valuable as it was to you after your full day hike?

I’m talking about motivating operations (MOs). “Motivating operations influence the current value of a consequence and therefore the frequency of the behavior that would contact that consequence” (The Dog Behavior Institute). DBI has a great post on MOs and one on the difference between a motivating operation and a discriminative stimulus if you want to learn more.

A few people have asked me how I chose “Ewok” as Sully’s new recall cue. In terms of criteria, I wanted the cue to: 1) Delight me (listed as number 1 for a reason); 2) Be something distinct that didn’t get used regularly in everyday life (really didn’t want to dilute it); 3) Be easy to say (aka no words that I might trip over trying to say); 4) Avoid causing harm to people when yelled out loud (i.e. don’t want to be yelling something that makes other people uncomfortable). Plus, before we got Sully’s DNA results, we assumed she was part Ewok. We still kind of think she is.

With Sully, the value of my treats in a given moment influences how likely she is to orient to me (or recall in the future) since that’s the behavior that leads to treats. I want to do everything I can to up the value of those treats (well, not everything … I am not going to use deprivation and starve Sully before training).

I play with MOs a bit to help myself out (and to be kind and care for Sully’s needs). We’ve been doing most of our attention training on our morning trail walks, and I let her walk for at least 20 minutes without any interruption from me. If she happens to offer me attention, I may** reinforce with a treat, but I am not going to pause to play games until after that 20 minute mark. I want her to “get her fill” of nature first so my treats might go up in value a bit relative to nature.

Imagine you’ve been sick and trapped indoors on the same couch for five days, and you feel like you’re going to lose it if you don’t breathe some fresh air. Getting outside has become REALLY valuable. Now think about Sully who has been “trapped” indoors all night as we sleep and desperately wants some nature in the morning. She’s been “deprived” of nature for the night and it’s value is quite high first thing in the morning, which means my treats are likely lower value relative to it. The value of my treats go up as she spends some time in nature and isn’t feeling so deprived of time outdoors.

**The reason I said “may” is because Sully’s eating behavior is a bit more fragile than many other dogs I work with. I had to work hard to get her eating behavior to show up consistently outdoors, and a big part of our success stems from my not offering her food when she’s likely to refuse it (I don’t want her to rehearse that behavior). In the first part of a walk, the environment is so high value that it’s hit or miss whether she’ll eat. I make a decision whether to drop a treat or not based on what exact behavior I’m seeing in her offered attention and what’s going on in the environment. After we get about 15 minutes in, it’s usually pretty safe to assume she’ll eat.

How Will I Know If My Training Is Helping?

Data!!!!!

Sully’s baseline for offered attention or check-ins on walks was basically zero. If I am actually reinforcing attention, I should see more of it under similar conditions moving forward.

My dog Otis regularly comes up to me on walks “asking for treats.” I want to see some of that from Sully to feel more confident that I’ve got a reinforcer that can actually do some reinforcing!

Here’s the good news: She offered us (me or my partner, Ben) attention on this morning’s walks FIVE times. That’s a 5x increase given that we started at zero. (Note: This count does not include instances of attention that are a part of the structured games we play.) AND, she even turned away from something in the environment and voluntarily ran to me (this was at the end of the video I shared on Instagram). This could be a fluke, but I don’t hate what I’m seeing … !

A Brief Reminder: You Don’t Always Have to Be Your Dog’s Priority

I want to be clear that I am not trying to turn Sully into a dog who is always focused on me. I love Sully’s love of nature. I am constantly checking myself as I train to make sure I am not depriving her of what she needs to thrive (time to “independently” explore nature being a key part of that). She never has to “earn” the ability to sniff or move around, and I still want the bulk of the walk to be hers. I am just seeing if I can get a few more tiny moments where she connects with me and then returns to the rest of nature.

More to come!

Back To Basics: How To Train Your Dog to Recall

Have you ever felt like you're talking to a wall when you call your dog to come to you? I realized a while ago that my little dog, Sully’s, recall had gotten worse. After some thought, I decided to start completely over with recall training, and I’m inviting you along for the ride.

What Is Recall?

Recall is the term used to describe a dog coming to us when we call them. In reality, the “recall behavior” is actually multiple behaviors performed sequentially. Those behaviors may vary a bit depending on what the dog was doing, what you cued, and when/how you marked and reinforced.

Generally speaking, when you call your dog to come, your dog will: Stop moving (if they are moving away from you), turn towards you/orient to you, run to you, stop when they get to you, and station in front of you (aka sit or stand in front of you). I often simplify this to: 1) Orient to you; 2) Move towards you; 3) Station by you.

By thinking about individual behaviors that make up a dog’s recall, we can really hone in on strengthening those component parts, which can help us build a stronger overall recall.

Understanding the individual behaviors that make up the broader sequence of behaviors we label “recall” is incredibly helpful in training. We will loop back to this in the future!

How Do You Get Your Dog To Come When You Call Them?

For now, let’s start with the basics.

When you call your dog to come, are they coming just because you asked them to? Sorta ... But not exactly.

Have you heard people say that “reinforcement drives behavior”? Whether or not your dog comes when you call them is determined by what happened under similar conditions in the PAST after they came to you.

The most basic unit when talking about operant behavior, which is voluntary behavior that is increased or decreased as a function of its consequences, is the Antecedent - Behavior - Consequence (A-B-C) unit. You want to start by defining the behavior you are looking at. The antecedent and consequence are stimuli or events that happen in the behaver’s environment. The antecedent comes before the behavior, and the consequence comes after the behavior.

“Come” is an example of a cue (in this case, a verbal one). When you call your dog, it signals the opportunity for them to access reinforcers (like treats) if they come to you. In other words, your recall cue (e.g. “come”) tells your dog what behavior-consequence contingencies are in play.

Here’s a human example of how cues work: When your phone rings (cue), if you answer it (behavior), someone on the other end will talk to you (consequence). Your phone ringing signals to you that the behavior-consequence contingency of “if you answer the phone, someone on the other end will talk to you” is now in play. If you answer the phone when it’s not ringing, there won’t be anyone on the other end who will talk to you.

So … your dog isn’t recalling simply because you told them to or because “they know what the word come means.” How they respond to your recall cue in the present moment is determined by what outcomes their behavior produced in the past under similar conditions.

This gets more complicated. For example, there are a lot of factors that may change how motivating a particular consequence is. I talked about this using the same human example as above (phone calls) in a recent Instagram post if you want to check it out.

We’ll leave it here for now.

Is It Harder To Teach Some Dogs Recall?

It might help to know a little bit about Sully. She is my great humbler, and I probably don’t thank her enough for all that she has taught me. She is not an “easy dog” in many ways, but I can rest easy knowing that the same behavior principles that apply to every other living animal apply to her.

Someone once described her as a “bloodhound in a terrier-like agile body,” and I thought that was fairly accurate (though I don’t think it fully captures her “prey drive” behaviors … in quotes because there is far more to it than “drive,” but I am not going to get into it here). Long story short: she finds the environment SUPER reinforcing.

When I say I say Sully loves the outdoors, I mean she is literally one with nature. I am competing with the dirt we walk on. I’d like to tell you that it’s rare that she gets herself this dirty, but that would be a lie.

On top of how much sniffy-hunty behavior she does, I struggled at first to even find reinforcers I could reliably use. When I first adopted her, she wouldn’t eat treats outside (she would occasionally, but not consistently enough to do anything meaningful with them). Someone might have labeled her “not food motivated,” but it was more so that the relative value of food went down when outdoors and she didn’t have a big reinforcement history for eating outside. I had to spend a fair bit of time just working on eating outdoors in a range of environments before I could even consider using food as a reinforcer for other behaviors like recall, which I worked really hard to build with her.

So with all of that said, my very honest answer is this: Yes, I do think it’s harder to teach some dogs to reliably respond to your recall cues than others. Dogs have unique learning histories and may find different things reinforcing.

BUT, that doesn’t mean that it cannot be done or that “positive reinforcement won’t work because a dog is [insert whatever breed you want].” The strongest recalls are built by creating big reinforcement histories for coming when called. Did you know that discretionary effort is one of the unique side effects of R+?

The phrase discretionary effort comes from the work of Aubrey Daniels, a behavioral psychologist who specializes in applying behavior science principles in the workplace.

With some dogs, we may just have to be more aware of what the dog finds reinforcing, what antecedents are at play (i.e. motivating operations), and how we move the recall behavior into new settings. Some dogs may tend to find treats WAY more reinforcing than nature, and that can make it “easier” (perhaps more “forgiving”) to build solid recall.

I know how to train recall (I LOVE doing it), and I still find myself in a position where I have to start over … which is okay! So please know you are in good company if you find yourself there too.

Why Am I Starting Over With Sully’s Recall?

Put simply: I don’t want to fight the learning history she has with her current recall cue (“come”).

It has become hit or miss whether she’ll come when we call her, and if she does come, the latency of the behavior is often high and the speed is often slow … not what I’m aiming for 😅.

Here are the three main measures of recall I’ve been using:

1. Does she come when called (defined as coming all the way to me)? This is a Yes/No data point. I should be logging mostly “yesses” here, but she was not coming at all when called about 50% of the time.

2. How quickly does she START to come to me after I call her (this measure is called latency)? I measure this in seconds. I want her recall behavior to be LOW latency (aka very short time between me calling her and her starting to come). However, I was seeing pretty high latency behavior (i.e. when I called her, she would often take 4 to 7 seconds to start to move towards me).

3. How quickly does she complete her recall behavior (this is called speed)? The amount of time it takes for her to travel all the way to me is going to vary depending on how far away from me she is when I call her, so I am typically rating her speed as slow, medium, fast, or lightning fast. I was getting a lot of slow and medium recall speeds, which isn’t what I am aiming for.

Her recall used to be much better than it is right now, so what happened? A number of things could have happened.

We could have inadvertently punished her recall behavior by following it up with something aversive (which is defined as anything an individual behaves to escape or avoid). An example of this might be using your recall cue at a dog park and then leashing your dog to leave the park or calling your dog to come and then picking them up to put them in the bathtub. Those examples aren’t fitting for Sully, but punishment still could be at play.

Perhaps more easily done than punishing recall, we might not have actually been reinforcing her recall when we thought we were. Just because you deliver a treat does not mean you reinforced that recall – you only know you reinforced it if you see the behavior strengthened or maintained in the future under similar conditions … and we are not seeing that play out.

What I feel confident we did was use her recall cue in situations where she couldn’t perform the desired behavior (aka immediately and with speed run to me). To be clear, I know the rules here (only use the cue when confident the dog can respond), but Sully is harder for me to make predictions with (the value of food is a lot less static than it is with many dogs and the environment is just SO interesting), so plenty of these instances were just accidents (i.e. I thought she was gonna recall). Though to be clear, plenty of the instances were just me and my partner, Ben being sloppy (and maybe a bit greedy) by calling her when we had no business doing that 🤣.

To some degree, she’s likely learned that her recall cue is irrelevant under certain conditions (it’s basically just become background noise that doesn’t signal anything meaningful for her). We used the cue too many times without a response, so that means the cue didn’t lead to a reinforcer all those times … so it’s just weakening more and more.

She now has a huge history (that I don’t love) with the cue “come,” and I’d be fighting it if I wanted to use that cue in my training to try to change her recall behavior. I don’t want to fight her history, so I am creating a new recall cue, Ewok (because she looks like an adorable Ewok) and starting at square one. This allows me to get the desired behavior (immediate response and fast run to me) and slowly move it into new conditions (more on this in the future)!

How Do You Start Teaching Recall?

There are a lot of ways to start, so I am going to talk about how I started (or restarted) with Sully.

As a reminder, before I did any training, Ben and I agreed on Ewok as our new cue (because I didn’t want to fight the history with the old cue). A part of my criteria for picking a new cue was that it had to delight me 😅. Then we agreed not to use her recall cue in real life yet to avoid “ruining it” before it’s even ready to dazzle. In the meantime, we’re leveraging long lines, drag lines, and informal prompts like kissy noises and “pup pup pup.”

I chose to begin by doing something called a stimulus-stimulus pairing. Put simply, I’m creating an association between two stimuli: the word “Ewok” and treats. You may have heard this talked about in dog training as classical or pavlovian conditioning.

Ewok → Treats

In this session, I simply said “Ewok” and then delivered treats (I did this about 15 times). She wasn’t required to do any behavior to get the treats. I delivered treats after I said “Ewok” 100% of the time regardless of what she was doing.

In the Instagram post I shared on this session, someone asked a great question, “I noticed that [Sully] was constantly looking at you. If you [said] Ewok and she was looking some other way, would you still give her the treat??” The answer is YES. But this person’s keen observations hint at why this stimulus-stimulus pairing procedure can be a great place to start your recall training: BEHAVIOR IS HAPPENING. I am using this pairing procedure to help produce operant behavior (voluntary behavior that is increased or decreased as a function of its consequences). In future sessions, I will adjust how I am using the treats. Instead of treats being delivered every time after I say “Ewok,” they will be delivered after I say Ewok and she performs some aspect of the recall behavior. Because I hope to train errorlessly, it may not look all that different at first, but it will in time!

The Secret Ingredient

Sometimes you hear people talk about using lower value treats in less distracting environments, but I am actually using the best stuff I’ve got in our first session.

One of the things I do when I want something really high value is cook some ground beef in a skillet. That isn't a typical treat that we use, so the novelty adds some extra value!

Here’s why: Take away the idea of your recall cue for a moment, and just imagine how your dog might respond to you holding out the most delicious food for them to eat (maybe a nice big steak or piece of salmon). Are you envisioning your dog flying over to you with “enthusiasm” (aka more effort than needed since walking slowly would have worked too)? I want to bring THAT behavior and those emotions to our recall, and high value reinforcers help me with that.

I cooked specially seasoned chicken and ground beef, and I asked Ben not to pull from those treat containers right now in everyday life because I want the boost in value that novelty can give reinforcers. (To be clear: I train her with food in her belly, and she still gets plenty of other high value treats in everyday life. I am not a fan of using deprivation generally speaking. I am simply using a treat that I wouldn’t otherwise make for her to take advantage of novelty’s effect.)

Questions From Our Community

I’ll try to pick a question from Instagram to highlight and answer in this section (or at least respond more thoroughly to … not sure “answer” is a fair word). I am basically thinking out loud here, so consider yourself warned lol!

Question: “Thank you for another wonderful post! I'm struggling a little bit with the idea that you used the recall cue too many times when Sully couldn't perform the behavior - I understand how this could spoil the cue, but it also seems to me that the times when recall is most useful/important is in those difficult moments. My dog also finds the environment heavily reinforcing, with a high prey (or at least chase drive) and what appears to be an insatiable curiosity about everything! She has very good recall at the dog park, but I don't let her off-leash anywhere else, fearing that my recall cue might not work if she came across a wild animal that she wanted to investigate or chase. How do you determine if your recall cue is ready for these situations? Do you think it ever can be for a dog with such high interest in the environment?”

Answer: This is a GREAT question. Have you ever heard someone say that your dog needs to be able to recall 100% of the time (“have perfect recall”) before you let them off leash?

But here’s the plot twist: While that old advice is meant to keep dogs and people and wildlife safe (or that’s my interpretation), I actually think the bigger threat comes from believing that any dog’s recall is 100%. I almost do the opposite of that old advice when I make a decision to let my dogs off leash: I assume my dogs will not recall. By making this assumption (or at least playing it out in my head), I can assess how big of a problem it would be in a given area if my dog blew a recall. If the risk to my dog and/or others is too high (and people will have different ways to evaluate risk and different risk tolerances), I don’t let my dog off.

For example, my other dog, Otis, has GREAT recall. But I don’t let him off leash if we are near a busy road. That isn’t because I think he will fail a recall. It’s because I cannot predict the future with 100% certainty, and the consequences of a failed recall are way too dangerous in that setting. I’m flipping the lens a bit and instead of focusing first on how likely my dog is to recall, I’m first focusing on how problematic it would be in the area we occupy if my dog didn’t recall. This actually helps take a lot of the stress and uncertainty out of my decision because all of the weight isn’t on my dog to recall perfectly in that setting.

Let’s chat about this point from the original question: “ … it also seems to me that the times when recall is most useful/important is in those difficult moments.” PREACH. I hear you loud and clear. This is what makes it so tricky to build recall. It also allows us to dive into the next decision layer with unclipping a leash. We have to have a pretty good understanding of our dog’s behavior and be able to read the environment well in order to make predictions. I would be remiss if I didn’t call out here that I have clearly failed at this since I am starting over 🤣. It’s so easy to blurt out your recall cue in a difficult moment and just cross your fingers that it works.

As you are building the recall, you will butt up against this line a lot. I actually think it’s easier at the beginning of training because the line is a lot clearer - you can basically assume the dog is not ready for any real life tests yet. For right now with Sully, my rule is not to use her recall cue at all in real life. It gets harder the more training progresses because that line gets a bit blurrier. (I do think this is where my decision making process for unclipping a leash helps.)

Let’s chat about the next part of the question: “How do you determine if your recall cue is ready for these situations?”

This can be tricky, and there isn’t one right answer. To some degree, the human’s risk tolerance is a factor. I don’t think I have ever written this out before, so I don’t think this will be perfect … my confidence level stems from some combo of these things:

1) My dog’s experience recalling under similar conditions.

In the course of training, I will systematically work in a variety of environments and with a variety of distractions. I will collect data (often in my head, but this time I hope to do it on paper) to help me determine what Sully is ready for. For a good long while, I will only use my recall cue when we are out and I want to get a recall rep in. I won’t likely use it in random, tough moments (I’ll accept that she may dip for a second and breathe knowing that I dropped the leash because I was okay with this happening here). I will only use my recall cue in real life when I think she has the learning history needed to respond by coming to me. I won’t be able to work directly with every tough distraction in controlled ways (e.g. deer), but I can set up similar conditions that I can control to work on recalling out of chase (like recalling off chasing a ball or a prey-like-toy on a flirt pole). If my dog has been able to recall mid-chase in a variety of contexts that I controlled, I have more confidence than I would otherwise (still not perfect) about recalling out of chasing other things in real life. If my dog has no experience recalling when they are mid-chase, I am not going to use a recall cue when they are chasing a squirrel. (More generally, I might also think about how many successful reps of recall my dog has done in total to gauge their overall R+ history. This is more relevant early on in the training journey.)

2) My dog’s past behavior around this distraction while on a long line.

For certain tough distractions (like deer) that I can’t easily control, I may use real life moments when leashed to train and gauge my dog’s behavior. For example, I want to see a dog quickly and easily respond to me when they see a deer while leashed before I ever consider recalling them away from deer when off leash. I might even see a dog spot and deer and automatically orient to me, which is the first part of recall anyway! I might take a dog to a spot with squirrels where they can practice just watching them (rather than chasing). These types of experiences around tough distractions give me a lot more confidence about recalling away from them if/when the time comes.

3) My dog’s offered behaviors.

This may not seem as obvious, but how my dog typically behaves in a given environment can contribute to my overall sense of confidence. For example, if my dogs have learned (generally) to stay on the trail, I may feel more confident than if they hiked by zooming around 100 yards off the trail. If my dogs auto-check in (aka stop and wait, look at me, and/or run back to me) as soon as they hit a certain radius from me on the trail, I might feel more confident than if they just keep running ahead. Right now, Otis’s typical trail behaviors inspire far more confidence than Sully’s. As soon as Otis gets about 20 yards away from me, he automatically stops or runs back to me. He is checking in all the time. Sully may walk for 45 minutes before she even looks at me 😂. Otis is essentially already performing the recall behavior - I would just have to add a cue in front of it. Most of the time, Sully isn’t offering any recall behavior (not even the initial components of it). I want to see pieces of that behavior showing up in the context of the environment before I try to cue it verbally. I will be working on offered check-ins on trails with Sully before I use her recall cue. (This can also give me info about whether my reinforcers are strong enough or not.)

4) Response checks.

There are a range of simple behaviors I will use to gauge what’s going on with a dog on a given day and in a given environment. For example, I might cue a nose touch, sit, and paws up. If those are behaviors that my dog can reliably do in a range of environments, I would know something is up if suddenly they can’t do them or they perform them slower. With Sully, one of the behaviors I will always check is whether or not she can eat. If she isn’t enthusiastically taking a treat I drop for her (or isn’t then looking up at me to ask for another), that is not a good sign about how motivated she’s likely to be to recall. Data like this can help me feel more confident in my choices.

5) Distant antecedents.

What has or hasn’t happened lately in my dog’s life that could influence their behavior or the strength of reinforcers? Here is a good example: We live near the woods and have a fenced back yard that Sully is able to patrol all day. When we stay at my sister’s house in Atlanta, she loses that activity for a week. When we come home, the deprivation can make her sniffy-hunty behaviors WAY more likely since the value of the associated reinforcers went up (because of the deprivation). So when we first return home, I hold her long line for a while and don’t recall her until she has her fill of nature again so my reinforcers can compete better with nature.

I heard something from a conference a while back that may be helpful as a framework (I wish I could remember the speaker’s name and exactly what they said). Write out a list of environments that are easy, medium, and hard in terms of level of difficulty for a recall. For example, here are Sully’s: Living room (easy), empty field (medium), woods (hard). I have expanded on this a bit and actually have a list of easy’s, medium’s, and hard’s. Then write out a list of as many distractions that you might recall your dog away from as you can think of going from easy to hard. For example, at the bottom (easy) end of the list might be a jacket on the floor and at the top (hardest) of the list might be a screaming fox running away. There are a lot of distractions between those two. Then you can start working through the distractions somewhat systematically to build the learning history you want with them. This can give you some confidence you might not have otherwise and help you decide when to let your dog off leash.

Now to be fair, I only worked through certain distractions (like recalling away from wildlife, recalling away from food, etc.) super systematically with my dog, Otis. Otherwise, I got to be a bit loosey-goosey and focus on building a big R+ history in general while still being intentional about when I used my cue. With Sully, I am going to be WAY more systematic (hello data collection!) – in large part to set myself up for success since I have a history of inaccurately predicting whether or not she will recall (or just throwing out hail mary’s).

Now to the final part of the question: “Do you think [recall] ever can be [ready for difficult moments] for a dog with such high interest in the environment?” To be honest, I don’t know. I don’t think I will ever trust Sully’s recall the way I trust Otis’s recall. She finds different things reinforcing than he does, and I have a harder time beating the environment with Sully. And I think that’s okay! I am going to make very different decisions about where Sully vs. Otis can be off leash. I still have safe ways to get her off leash time in fenced spaces and can use long drag lines in areas that are not-populated and very far from roads. There are MANY ways that I can work with some of her predatory behaviors, so I’m sure we will make progress. How that progress translates to my decision making is yet to be seen, but I have a hard time believing that I will ever feel as confident in her recall as I am in Otis’s.

This leads me to a final closing thought. Sully is going to fail recalls during this training journey. While I am going to use an errorless teaching approach, failures and mistakes are a normal part of the process. As we progress and the recalls get harder, I am going to make mistakes in my predictions and call her in moments when she can’t recall. To some extent, those failed recalls give me really valuable data that inform my training and helps me sort out where our gaps are. I won’t be using her new recall in real life anytime soon, but when I do, I am going to have to give her a little bit of freedom in order to recall her (it’ll be freedom on a long drag line). It’s a tough thing to balance!

Stay tuned for more!

Training Diary: My Journey to Figure Out How To Put a Cone on My Dog (Intro)

Editor’s Note: Rather than a formal guide, this blog is very much in the vein of a journal entry. I may adapt the style a bit as we go, but for now, I went with providing a simple peek into my thinking.

Hi friends! I’d like to start by saying that I feel a funny mix of “let’s have some fun” and “please direct me to the nearest hole to crawl into” as I begin writing this. Why?! Well, in the process of trying to put a cone on my dog, Otis, after a surgery, I made a billion mistakes that forced me to have to do this work. And then I made a ton more mistakes. AND I am not done. So yep, that about covers it.

I’m going to do my best to share training videos and talk about what I was thinking about that led to some of my choices. Let me be clear: I didn’t always make the best choice first. I also needed help! While this journey happens to be cone related, I think a lot of the lessons can be generalized more broadly. My hope is that we can use my journey (it’s easier to pick at my own work) to help ground many of the concepts you hear us talk about in training. I REALLY want this series to be a conversation, so PLEASE ask questions, share stories, etc.

How My Journey Began to Figure Out How To Put a Cone on My Dog

Otis is the dog who turned me into a trainer. As you might suspect, I would like a re-do on a great many things. He’s a sensitive soul, and I didn’t condition a cone before he got neutered (and had a gastropexy) years ago. TIP: Absolutely condition whatever you plan to use post-surgery beforehand (don’t make my mistake)! When I picked him up from the vet, they told me they couldn’t keep a cone on him. I had no luck either (and risked him tearing all the new sutures). I tried a donut and couldn’t get within 15 feet of Otis.

Fast forward a couple of years: I started to condition the cone as a “just in case” measure. Relative to “I won’t be in the same room as a cone,” we made progress, but we always stalled out at the same point (and then I’d stop working on it). I had a “moment of clarity” last fall when I just knew I was going to regret it if I didn’t sort this out now. With much more knowledge than I had before (including the wisdom to bounce ideas off people), I got started!

Who Is This Training Diary Series For?

Anyone! While I am going to show you how I approached a specific problem/goal related to a cone, the concepts at play apply much more broadly. For example, one of the issues that led me to getting stuck at the same point every time was that I was doing something called “lumping criteria.” I had to break it down WAY more than what I was doing in order to make progress. This is a truth that applies in most every training endeavor.

Training Diary: My Journey to Figure Out How To Put a Cone on My Dog (Session One)

Editor’s Note: Rather than a formal guide, this blog is very much in the vein of a journal entry. I may adapt the style a bit as we go, but for now, I went with providing a simple peek into my thinking.

What do you do when you get stuck at the same point in your training every single time? Well, if you’re like me, you might avoid training for a while, but then you eventually go back to the drawing board. If you missed the context for this series, basically I need to get my dog Otis comfortable with wearing a cone just in case he needs to wear one in the future. You can read more background here. In this article, I am showing you footage from the very first session of my “re-imagined” cone training plan and walking you through some of my thinking and observations. This isn’t a “how-to” for getting a cone on your dog (in fact, my best tip is to work on this FAR before your dog develops an aversion). This is what I did for one dog in a specific situation, but I hope that by thinking out loud, it will give you some ideas (whether your challenge is a cone or something totally different).

My Process of Thinking About My Behavior While Trying To Put a Cone on My Dog

Here you can see my rudimentary setup, where my wire “cone” is suspended in my hallway over a blue yoga mat.

In previous training attempts, I spent so much time thinking about the behavior I wanted Otis to do (“put his head into a cone” and “wear a cone”) and very little time thinking about my own behavior. As a great mentor, Laura Monaco Torelli, taught me, very often the behavior we are asking of our dogs is simple. We are just asking them to perform that behavior in a huge range of conditions. Functionally speaking, the behaviors needed from Otis in order to wear a cone are pretty simple.* But what is going to happen around him in the environment is far more complex. So this go around, I focused on every little component piece of environmental events that Otis would experience as a part of “wearing a cone” (just not all at once!).

*At the most basic level, I needed Otis to be able to stand and to eat a treat. However, I did note all of the behaviors I wanted Otis to be able to do while wearing a cone (like walking outdoors, moving through the house, lying down, eating, drinking, etc.) because that would factor into future training.

My Approach to This Cone Training Session

Here’s a closer look at my makeshift “cone” with Otis resting on the couch in the background.

From my prior experience in working with my dog and cones, I identified two big problems that contributed to us getting stuck in our training: 1) Any movement of the cone around his head; 2) Taking my hands off of the cone once his head was in it.

I decided that I wanted to focus on breaking down the two big problems I identified. I knew I couldn’t start with a cone without lumping criteria, so I had to think of a way to break it down. A cone tends to move around a bit as the dog moves, so I wanted him to experience some subtle but unpredictable movements with a less intense object near his head. I decided I wanted my hands out of the equation to start because I wanted to give him as much control as possible (while I’ve tried hard not to force things on him throughout his life, he knew that my hands could move). Otis makes progress much much faster when he has as much control as possible (something that is not unique to just Otis 😉).

So I found an old wire hanger and bent it into a circle. I wrapped the metal circle I made in a towel to make it softer. I made the circle larger than the opening he would have if he were wearing a cone or donut to reduce the intensity he experienced when putting his head through it.

Then I had to come up with a way to hold this circle up in the air without using my hands. I wanted the circle to move a little bit but not a ton. The reason I didn’t want it to be perfectly still is that I wanted him to learn up front that the circle moves a bit and make choices based on that understanding. I attached four small ropes to the circle and rigged up a suspension system by attaching the rope to the inside of doors in the narrow hallway in my apartment. To start, I tried to have as much tension as I could on the ropes to limit movement (knowing that it would move no matter what because of my design).

There are a million ways I could have started the actual training session with him. Two more amazing trainers influenced how chose to start: Kiki Yablon and Hannah Brannigan. I sent Kiki a picture of the absurd setup that I had created and said I was a little nervous that I was going to mess this up from the get-go and have to come up with a totally new picture. She sent me one of Hannah’s videos where she starts a training session by teaching the dog (non-contingently) where the treats will show up for the session. Kiki said she often starts harness desensitization by first teaching the dog that treats show up through the harness. I remember telling her that I was worried about doing that because I didn’t want to create a conflict by making him do something “scary” to get food. As Kiki is apt to do, she reminded me that I could observe and adjust … and that I could stick my hand all the way through the ring to start rather than asking him to bring his head through the ring.

With a plan on how to start, I laid a yoga mat out (so he would have secure footing), set the camera up (so I could re-watch the session and see what to adjust next time), and began.

My Observations From This Training Session

Note: My bullets below that reference times in the video may be off by three seconds or so.

Apprehensive at first - When Otis first approached the circle, he stayed fairly far away. He was reaching/leaning forward rather than just approaching it, and in this context, I read his behavior as showing a bit of concern. I repeatedly clicked and then reached my arm through the circle to give him a treat. I reached far through the circle at first and gradually reached less (I tried not to force him to come closer too quickly).

Yoga mat - While I thought to put a yoga mat out, I didn’t align it correctly, so his back feet slipped on the wood floor. Imagine not being comfortable around something new in your environment. Are you going to feel more or less comfortable around it if you feel like you can’t control your movements? I would argue less.

It moves! – You can see him learn that the circle moves. He was really “jumpy” in response to the circle’s movements at first.

Nose boops - He tapped the circle with his nose a couple of times. I wasn’t sure if he was trying to gather info about the circle or if he was offering a behavior trying to get a treat. In the early stages, I was really trying to non-contingently give him treats through the circle to teach him where the treats showed up. I didn’t actually want him booping it too many times because I didn’t want this setup to cue booping when I knew that later I was going to shape him to put his head through it. I still gave him a treat for the nose boops, but I didn’t mark.

Rate of reinforcement - I chose to speed up my rate of reinforcement to try to prevent the nose booping altogether. Looking at the video now though, I probably fed him too quickly because I was marking before he even finished eating the previous treat. (Mechanics are hard 😅.)

Treat placement - I gradually delivered the treats closer to the circle. I still delivered treats non-contingently for quite a while (aka he didn’t have to do a specific behavior to “earn” the treat). (NOTE: I say this but there is always SOME behavior happening that I am reinforcing. I just wasn’t really selecting for anything yet … aside from maybe eating the preceding treat from my hand through the circle.)

Moved yoga mat - At about a minute, I got smart and scooted the yoga mat so his back feet would land on it too. I tossed a treat away while I moved the mat, and when he returned, he basically stuck his head through the circle!

Offering behavior - He started to offer some movement towards the circle on his own. I think he got a little startled (sharp backwards movement) by the circle moving and stopped offering forward movement towards the circle.

Treat placement - I switched back to non-contingently delivering treats, but this time, I started to deliver them ever so slightly on my side of the circle. This meant he had to stick his head in a little bit to get the treat.

Wonkiness - At around 1:30, the circle moves, he backs up and boops it a few times. I maybe asked too much of him before this. Maybe he was gathering info. I didn’t want to push him, so I delivered a treat on the ground a little closer to the circle. I probably could have just reset tossed away from him. I think in the moment I was worried about him deciding the game was to back up, but with hindsight now, I didn’t need to worry about that.

Adjusting to movement - At around 1:45 and later, he learns how the circle moves when he pulls his head out from it since I was now clearly delivering the treat on my side of the circle. He was super responsive to the circle’s movements – you’ll see his jumpy movements. He also seemed to really look at the circle. I really tried to notice where his attention was going – it gave me data about what cues in the environment mattered most to him. And for a good while, his eyes were locked on that circle (perhaps telling me that circle was a very relevant cue for him). I was non-contingently delivering treats for a bit after switching to delivering them on my side of the circle to avoid raising criteria in more than one dimension at a time.

Contingent reinforcement - At about 2:12, you will see him shift his weight forward towards the circle. I marked that. I started looking for him to offer me some movement towards the circle to mark & reinforce. He was now consistently doing this! At about 2:29, he got a little startled by the movement of the circle, and he pulled his head up and took a step back. Why? My best guess was so he could get a better look at the circle. After this, I marked the moment he chose to learn forward again even though he was farther away from the circle. To me, this was shaping “resilience” around a moving object! At around 2:33, he actually made the choice to stick his head into the circle even though it was moving quite a bit! This was cool! He took a few big steps back at 2:37, so I chose to give him a reset toss away (walking away is ALWAYS an option). After he came back, you will see him become a little less responsive to the movement of the circle, which was what I was looking for. He still had a few reps where he pulled his head out fast and watched the circle move, but more and more, he wasn’t attending to the circle as he moved his head in and out. He backed up one more time, and again, I tossed away to give him the choice to return or not (he returned).

Ending - By the end, he was rapidly sticking his head partway through the circle by choice and is not orienting to the circle every time it moved anymore. Earlier in the session, the circle’s movement was a very salient cue for him to back up and watch the circle move. Over the session, he seems to have learned something about that movement because his responses to it changed. And he recovered quickly if he did need to back away from the circle. From where we started, this was big progress!

What I Learned From Figuring Out How To Put a Cone on My Dog

Within four minutes, Otis went from staying far from the circle and leaning to get treats to sticking his head part way through the circle and not really responding to the circle’s movement around him. I was really happy with this! Because of the trend of his behavior during the session, I was comfortable sticking with the approach of showing him where the treats would appear (I think this sped up the session quite a bit). If his leaning/reaching had gone on for longer or he was not approaching the treats, I would have stopped this approach.

Did I maybe train for too long? Probably, but I don’t know. I will tell you that I thought about ending the session many times during these few minutes. A part of me thought I should end because I know that in general, shorter quality sessions are better. However, I thought that this was something that was going to require some time for him to adjust to the environment. I wanted to give him the space to do that. I worried if the sessions were too short, he wouldn’t have the time he needed to adjust. I honestly am not sure if I made the “right” call or not, but for us, it worked out.

How to Use the Dog Park to Train Your Dog

We love dog parks - just not for the reason you might think. Let us explain. Other dogs can be a huge distraction (or even a trigger) for your dog. Maybe you have a super social dog who pulls you on the leash toward other dogs. Or maybe your dog lunges and barks out of fear when they see other dogs. Or perhaps your dog simply has a hard time giving you any attention around dogs. In order to help your dog feel more neutral or be able to offer behaviors you want around them, it is really important to find opportunities to work around dogs where you can control the distance between your dog and the other dogs. And that is where dog parks can be helpful: the fence around the park becomes your teammate. Instead of going into the dog park, you and your dog can work outside of it -- adjusting your distance to meet your dog’s individual needs (or perhaps even staying in the car). It gives you the ability to work around distractions/triggers while keeping your dog under threshold. It is easy to focus on your dog engaging with other dogs, but what might happen if you shift that focus a bit to your dog engaging with you around other dogs? While this list is certainly not exhaustive, we wanted to share six ideas of simple activities you can try outside of your local dog park.

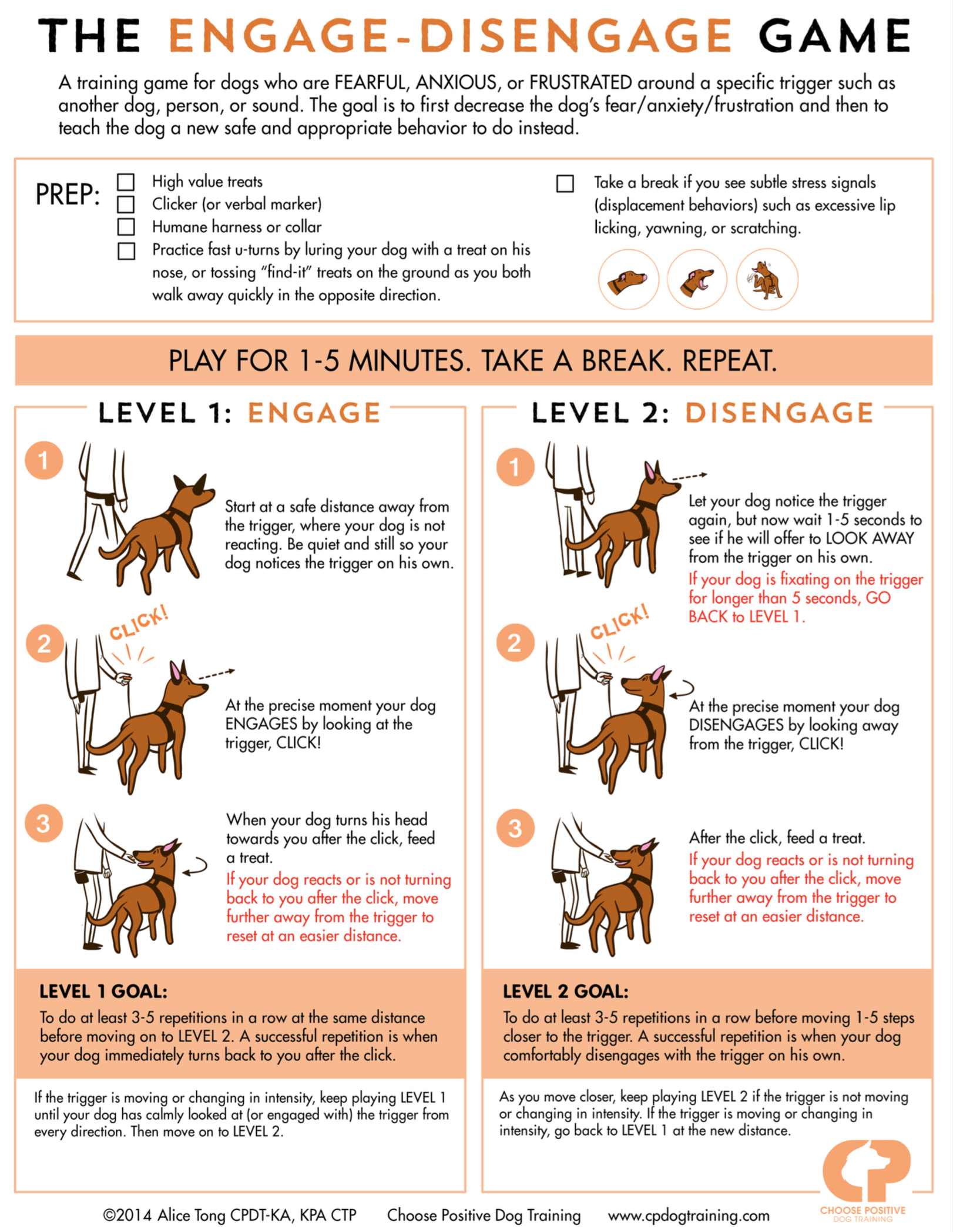

Play the Engage/Disengage Game Outside of the Dog Park

Engage/Disengage is a simple game that you can use in training sessions and in everyday life that will help change your dog’s emotional response to seeing other dogs. It will also teach your dog how to automatically look to you when they see a dog.

What: The game has two levels. In Level One, you mark the moment your dog notices/engages with the other dog. In Level Two, you wait for your dog to look away from the other dog and then mark and reward. Check out the infographic below for details.

Why: This “game” is simple and crazy powerful! This game will help your dog learn how to self-interrupt when they notice other dogs (or whatever stimuli you do this with) and will reduce the stressful feelings that come up. Engage/disengage will help make your dog’s new default response around other dogs be to disengage and look at you.

How to Practice U-Turns Away from Dogs Outside of the Dog Park

Sometimes you just need to be able to walk the other direction when you see a dog -- here is your chance to practice that!

What: Walk toward the dogs (aka toward the dog park). Say whatever cue you use to ask your dog to flip around and follow you (e.g. “let’s go”) and then turn around 180 degrees (avoid yanking your dog -- you want your dog to be responding to your cue and body language). Mark and reward your dog as soon as they flip around to face you. (Note: Practice this in a low distraction setting before you try it outside a dog park.)

Why: This builds a history of reinforcement for your dog for turning away from dogs and makes it more likely that they will be able to do this in everyday life settings.

Try the Cookie Toss Game Outside of the Dog Park

TOC co-founder, Christie Catan, plays the cookie toss game with Hana, the American Staffordshire Terrier Puppy, during a session for how to use the dog park to train your dog.

This may look simple, but the cookie toss game is powerful and can helps your dog choose to engage with you instead of with other dogs (or more broadly, the environment).